Why bonds go up and down

Bonds and shares have some things in common. They are both types of securities used by companies to raise capital. They are both initially offered in the primary market (i.e., purchased from the issuing company) and then traded in the secondary market (like on a stock exchange). And their prices go up and down on news.

But bonds and shares also have differences. While shares are a form of ownership, bonds are a type of loan issued for a set maturity – from less than one year to 30 years+. Unlike shares, bonds are issued by governments as well as companies. And bonds tend to be less volatile than shares.

Most asset classes have experienced price volatility in 2022. Bonds are no exception. In fact, it has been the most volatile period for bonds over the past 40 years as this graph shows:

Just like share prices which always bounce back after falls, so do bond prices. Let’s look at an example explaining why bond prices might fall.

Unlike shares, bonds offer a lot of information about future cash flows because they offer a fixed income stream via their coupon, which is the annual interest paid on the bond.

Bonds always have a purchase price of $100. Let’s look at what the cashflows would be for a 4-year bond issued by company called Nettube with a coupon of $2 per year:

In this situation, the yield of the bond is 2%, calculated as the annual coupon ($2) divided by the price ($100).

At the time of issue, the market believed the risk of the issuer not returning the $100 of capital after four years warranted a rate of return of 2%.

The main risk to the investor that the bond price may fluctuate over the next four years is if the market thinks the required return for holding a Nettube bond is no longer 2%. This could change because the company’s financial results change – either up or down – all macroeconomic conditions like inflation change – which is the story of 2022.

For every bond you can calculate the modified duration, which measures the average cash-weighted term to maturity of a bond. Through the wonder of mathematics, the modified duration tells us how the price of the bond may change given a 1% change in interest rates.

For the Nettube bond, the initial modified duration would be 2.0. If an unexpected inflationary event made investors say for the risk of holding a Nettube bond, they now require a return of 3% instead of 2%, then the modified duration of the bond tells us the bond price would fall from $100 to $98.

Whilst the Coupon for the bond will not change from $2 per year for four years, investors now want that $2 coupon to provide a yield of 3% per annum over the four-year period. For this to hold, the bond price must fall from $100 to $98. Put into a formula:

Annual coupon of $2.00 = 3% expected yield to maturity

Current Price of $98.00

So now, a $2 coupon for four years represents a 3% yield for a bond priced at $98.

For the investor who purchased the bond the day before at $100, they have an unrealised capital loss of $2.

However, if they continue to hold the bond for the four-year period, so long as Nettube remains in business after four years, they will still receive their $100 return of capital on the redemption date. The initial capital loss will eventually be recovered as the capital price rises from $98 to $100.

And what about investors who enter the market with cash now? They are buying bonds yielding 3% as opposed to 2% just a few days earlier. They are getting a higher expected return.

When bond prices fall, they can be attractive investments, particularly for people holding cash.

The scenario is what is happening in global bond markets now.

Whilst prices have recently fallen, by holding onto bonds there is now the expectation of future capital gains. And for people entering the market with cash, they can now purchase bonds with much higher expected returns.

Looking at the Dimensional Global Bond Trust we use in client portfolios, we can see some bond holdings paying coupons of 2.00% bought some time ago, and more recent bond purchases yield 5.25%. That is what we expect to see in markets like this – the expected return of the portfolio is gradually increasing.

It is still important to remember markets are forwards looking, but don’t always get it right in the short-term.

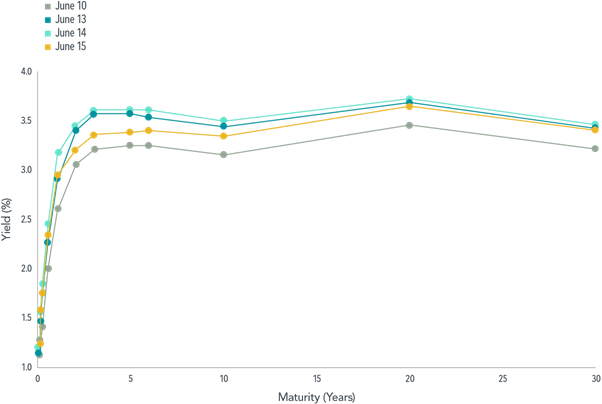

The US Federal Reserve announced 15 June its decision to raise the federal funds rate by 0.75%, the largest rate hike in nearly two decades. The market’s response? US Treasury yields actually fell slightly compared to the yield curve’s position on 14 June 14. This is not to suggest bond markets shrugged off the Fed’s actions. Looking at the yield curve over preceding days (see graphic below), it’s apparent the market was ahead of the curve—yields jumped from 10 June to 13 June upon signals from the Fed that higher-than-expected rate rises were coming. By the time the announcement was official, a 0.75% rate hike was old news to investors.

Some investors may also wonder if it is better to hold cash when reserve banks are changing interest rates.

The graphic below looks at the average annual return of government bond returns in excess of cash for the period 1984-2021 for four different currencies – USD, Euro, Japanese Yen and British Pound:

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

Across the four currencies, we find no reliable relationship between past federal funds rate changes and future government bond performance. In addition, average annual government bond excess returns were positive and similar in magnitude regardless of changes in the federal funds rate in the past year across all four major currencies. The analysis does not support the idea of allocating away from bonds to cash in response to changes in the federal funds rate.

In summary, 2022 has been a volatile year for bond prices. Any short-term capital losses will be recovered over time, and cash moving into bonds now will be yielding higher returns than over the past few years.

Author: Rick Walker